Your reference for hepatitis C in Quebec

An updated plea from the provincial HCV committee

As part of our mandate, we have updated our recommendations for achieving the WHO's goal of eliminating hepatitis C in Quebec by 2030. We have identified 7 actions that will help achieve these objectives. These updates are intended to complement our advocacy. In no way do they replace advocacy.

If you share our vision, you can show your support via our form.

You will find the full plea and reasoning below the seven actions:

*In this document, we specifically address the issues surrounding HCV, but it's important to note that the proposed actions encompass all SSTIs. Indeed, it is essential to adopt a global approach and work in concert to avoid working in silos, to be more effective and to promote better access to care for people.

- Adopt a Quebec strategy to fight hepatitis C and allocate the funds needed to implement it.

Quebec must adopt a national strategy to combat hepatitis C and allocate the resources needed to implement it. The first step in this strategy is to endorse the WHO targets to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030, Quebec being the only province or territory not to have done so. This strategy must be based on the needs identified by the communities most affected, and form part of an integrated approach to all STBBIs.

- Increase, improve and facilitate access to hepatitis C screening

In order to initiate treatment, people living with HCV must first know their status. It is therefore essential to develop screening services to make them more accessible. This means deploying new modalities such as community screening and new techniques such as self-testing or reflex tests. We emphasize that combined rapid tests for the simultaneous detection of HCV, HBV and HIV represent a very good opportunity to identify undiagnosed cases. Decentralization of services and delegation of tasks are recommended by the WHO to achieve its elimination objectives.1.

- Facilitating access to care for people living with hepatitis C by addressing systemic barriers

In the field, we observe difficulties in linking people to care following a hepatitis C diagnosis. For marginalized people, with precarious migratory status, living on the streets, stigmatized because of their drug use, their sexual orientation... the barriers are already numerous, and the crises we are experiencing (overdoses, housing...) only aggravate the situation. It is impossible to consider eliminating hepatitis C without addressing the consequences of social precariousness.

- Access to hepatitis C treatment for all, without exclusion

At a time when treatment for hepatitis C in Quebec is accessible regardless of the stage of fibrosis, and whether it's a primary or reinfection, we must continue our efforts to guarantee access to DAA for all. People with no medical coverage (RAMQ drug, IFH, NIHB) have no access to treatment or associated care.

According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, “At a minimum, Canada should guarantee public health care for all migrants in the event of infectious diseases, including access to screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up.”2

- Ensuring that harm reduction services meet needs3

People who use drugs are disproportionately affected by hepatitis C. This virus cannot be eliminated without harm reduction programs. As established by AQCID in January 2022:

"Funding Request: 25 million recurrent to save lives! An additional $10 million in funding is imperative, because Minister Dubé must put an end to this preventable hecatomb. This additional funding would make it possible to offer direct services adapted to the needs of the population, for a total of $25 million in recurrent funding allocated to community organizations working in the field of addiction and substance use. This measure would promote greater coverage across Quebec of key overdose prevention services, such as the operation of safe consumption sites, drug analysis services, naloxone distribution, and an increase in the number of street workers, among others."4

The government must increase funding and continue to adequately support the implementation of harm reduction programs by experienced community organizations.

These programs must ensure the distribution of sufficient quantities of consumption equipment (syringes, needles, pipes) in a variety of environments: among drug users, in prisons and on supervised consumption sites. At the same time, the decriminalization of drugs must be implemented, to ensure a more humane and health-conscious approach to this complex issue.

- Encourage and fund education and information sharing on hepatitis C and other STBBIs, with priority given to specialized Quebec organizations.

Knowledge is one of the most important means of prevention. In the case of hepatitis C, stigmatization comes from the general public, healthcare professionals and healthcare network authorities. Education and the sharing of verified information can frame and reduce stigmatizing beliefs. This step is recommended by the WHO as a common measure against HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections: “Essential interventions to reduce the number of new infections, in line with global targets, include those aimed at ensuring: greater access to scientifically accurate, comprehensive, age- and culturally appropriate education that offers adolescent girls and boys, young women and young men, according to their evolving capacities”.1. Indeed, without awareness-raising and education, stigmatization and discrimination become barriers to access to care for the people concerned.

- Collect Quebec-specific data on HCV prevalence, reinfections, etc.

In Quebec, we have little data on HCV prevalence, reinfection rates, etc. Although an estimate exists, it is difficult to specifically identify the rate of people living with hepatitis C in each region of the province. In order to provide clarity on the hepatitis C situation in Quebec and guide public health policies/strategies/actions so that they are adapted to the realities on the ground, it is necessary to collect quality data and make them accessible.

Conclusion

The WHO targets for the elimination of hepatitis C are achievable and attainable in Quebec. To take the first step towards this goal, the Quebec government must endorse these targets. Organizations working with communities affected by HCV and other STBBIs are deploying their utmost efforts within the limits of their capacities to achieve the above-mentioned actions. They are also prepared to do whatever is necessary to achieve the WHO targets. But without the moral and financial support of the Quebec government, hepatitis C will continue to slip through our fingers.

References

- Stratégies mondiales du secteur de la santé contre, respectivement, le VIH, l’hépatite virale et les infections sexuellement transmissibles pour la période 2022-2030, Organisation Mondiale de la Santé – https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/361200/9789240053816-fre.pdf

- Visit to Canada – Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, United Nations – https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ahrc4134add2-visit-canada-report-special-rapporteur-right-everyone

- The Global State of Harm Reduction 2024 – https://hri.global/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/HRI-GSHR-24_full-document_1411.pdf

- Maintenant plus de 1 décès/jour par surdose au québec et le ministre de la santé n’envisage toujours pas d’augmenter le financement afin de les prévenir. – AQCID – https://aqcid.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Communique%CC%81-de-presse-sur-les-surdoses-Janvier-2022.pdf

Plea: For Quebec community workers to perform rapid HCV tests

This plea is presented by Centre Associatif Polyvalent d’Aide Hépatite C (CAPAHC) and the Comité Provincial de Concertation en Hépatite C, a consortium of 31 community organisations based in 8 regions working with key populations affected by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Quebec.

It is intended to improve hepatitis C care and access to treatment by recognizing the essential role of community-based providers and allowing them to conduct rapid screening tests for hepatitis C antibodies at the point of service.

These rapid tests represent a tool for directing key hepatitis C populations towards a medical diagnosis in Quebec. Having these tests performed by community workers would improve and speed up the care of people living with hepatitis C (PLWHC) by the public health and social services network (Réseau public de la Santé et des Services Sociaux - RSSS). We maintain that this change is essential if Quebec is to achieve the World Health Organization's (WHO) goal of eliminating HCV as a public health threat by 2030.

- Support

- Overview

- Plea

- Poster presented at the Global Hepatitis Summit 2023

- Appendix - Community VHC projects

We are now looking for further support to show policy makers that HCV professionals support our approach. If you share our vision, you can register your support using our form.

- Valérie Martel-Laferrière, Research Physician, CHUM

- Louis-Christophe Juteau, Physician, CHUM, CIUSS Centre-Sud de l'Île-de-Montréal, Dopamed Community Clinic

- Caroline Fauteux, Specialist Nurse Practitioner - Front Line, Ciusse

- Maryse Cayouette, Microbiologist-infectiologist, CISSS de Lanaudière

- Serge Côté, Nurse, CHUM and CRCHUM

- Louis-Joseph Benoit, Intervenant, MIELS-Québec

- Katherine Pamela Gonzalez Reyes, SIDEP Nurse, Ciusss centre ouest de l’île de Montreal

- Dominic Martel, Pharmacist , CHUM

- Johanna Sincere, Nurse Clinician, CHUM

- Mariane Rondeau, Nurse Clinician SIDEP, CIUSSSE-CHUS

- Mylène Turcotte, Nurse Clinician, CIUSSS-Estrie

- Emmanuelle Huchet, Doctor and Medical Director, Clinique l'Agora

- Isabelle Thibeault, Nurse practitioner and regional coordinator of the integrated HIV and HCV network in Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean

- Suzanne Marcotte, Pharmacist at the CHUM

- Cíntia Soares, Research Officer at the CRCHUM

- Laetitia Grenier, Housing Sector Coordinator for Dans la rue

- Xavier Dreux, AIDES Project Manager

- Michelle Bergeron, HIV Community Specialist for Gilead

- Sofiane Chougar, Assistant Head Nurse - Addiction Medicine Service, CHUM

- Ju Massicotte, Content Coordinator, Portail VIH/sida du Québec

- Benoit Henry, Infectious Diseases Nurse, Correctional Service of Canada

- Caroline Gravel, Street work in the Brandon sector

- Martin Baril, Medical Scientist, Gilead Sciences

- Lisa Gauthier, VHC Community Specialist, Gilead Sciences

- Thuy Dao, Clinical Nurse, CEMTL

- Julie Cotton, Family doctor, CIUSSS Centre-sud-de-l'île-de-Montréal

- Marjolaine Pruvost, Project Manager, CAPAHC

- Patrice Vigeant, Microbiologist-infectiologist, CISSSMO Suroit

- Suzanne Brissette, Doctor, CHUM

- Julie Bacroix, Nurse Clinician, CHUM

- Katherine Dumont, Project C Community Intervenor, La Réplique

- Guillaume Tremblay-Gallant, General Direction, Portail VIH/sida du Québec

- René Légaré, Communications Coordinator, COCQ-SIDA

- Valérie Samson, Director, La Réplique Estrie

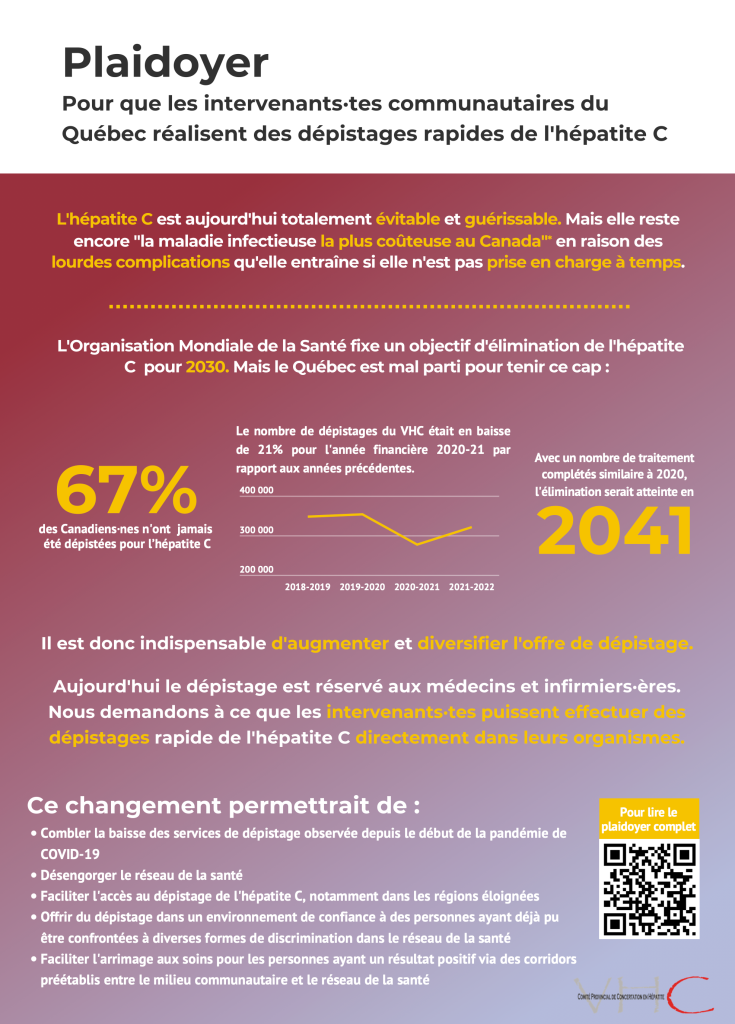

Hepatitis C is an infection of the liver caused by the hepatitis C virus. It is now completely preventable and curable. However, it remains 'the most costly infectious disease in Canada' because of the serious health complications it can cause if not treated in time. This is partly explained by the fact that 67% of Canadians say they have never been tested for hepatitis C and about one in two people living with hepatitis C in Canada do not know their status. This situation is particularly unfortunate given that the latest generation of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments allow for short treatment durations of 8 to 12 weeks, with success rates of over 98% and virtually no side effects for patients.

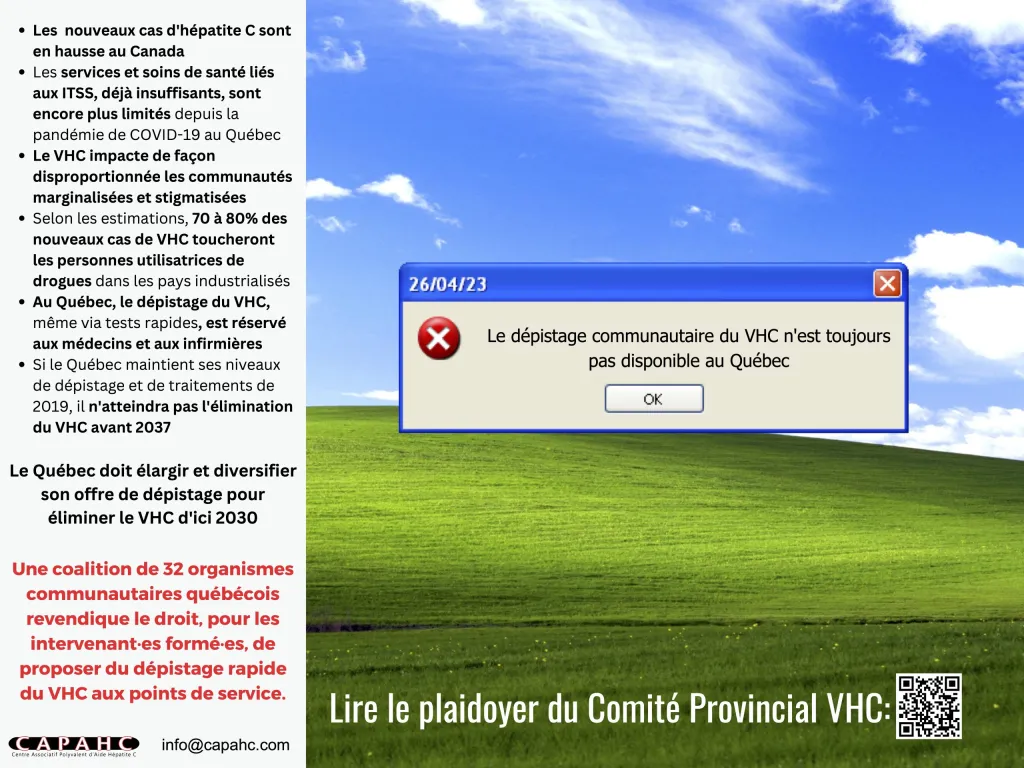

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of hepatitis C in Quebec was estimated to be around 37,000 cases. We also know that the national incidence rate increased by 14.4% between 2014 and 2018, from 29.6 to 33.9 cases per 100,000 people. We do not have the data to know how this incidence has changed since 2020, but we assume that it has continued to increase due to the reduction in testing availability during the pandemic, as RSSS teams usually dedicated to STI testing were ordered to offer COVID-19 virus testings. During the pandemic, people who use drugs had limited access to harm reduction equipment and services, and reduced or interrupted access to STI testing. In the same period, the number of overdoses rose sharply, according to data from supervised consumption sites. Before the pandemic, 85% of new HCV infections were among people who inject or inhale drugs. We now fear an increase in new HCV cases in a context of greatly reduced access to prevention.

We need to take rapid action against the spread of this virus, using all the tools at our disposal. Rapid HCV testing by community workers is a practical and effective way of combating the virus, and is one of the WHO's recommendations.

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a target to eliminate the public health threat of viral hepatitis by 2030. This will require diagnosing 90% of new HCV infections, ensuring that at least 80% of those diagnosed have access to treatment and are cured, and reducing HCV-related mortality by 65% compared with 2015 figures. These targets were reaffirmed in the WHO's Global Strategy to Combat HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Other STIs 2022-2030. In 2018, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) published a Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on STBBIs, which sets elimination targets for 2030 in line with those of the WHO, but does not include concrete measures and timelines to detail how these targets can be achieved.

A study published in 2022 estimates, based on a rate similar to that achieved before the COVD-19 pandemic, that Quebec will not reach its HCV elimination target until 2037. Worse still, if a rate equivalent to that achieved in 2020 were applied, the elimination target would not be reached until 2041. However, the study also estimates that a 10% increase in the number of new diagnoses and treatments compared with pre-2020 rates would enable Quebec to achieve its elimination target by 2031. This would prevent around 90 cases of terminal liver disease and 50 deaths, representing savings of $31.2 million for the Quebec healthcare system over this period.

To reach the WHO's 2030 elimination target, around 2,800 treatments would have to be completed each year, whereas in 2020 around 1,600 hepatitis C treatments were completed in Quebec.

It is essential, therefore, to diversify and increase the range of HCV testing services available in Quebec if we are to detect enough new cases to achieve the goal of eliminating hepatitis C as a threat to public health by 2030.

For the community workers who helped write this plea, the 'enemy' in the fight against HCV is often the medical appointment. Screening for the disease can take a long time, and patients are asked to return at a later date for testing, and then wait several weeks for the results. The result is that there is a loss of contact with many of these people before they can even be part of the RSSS.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of offering rapid testing at points of service, increasing the number of people tested and improving their engagement with the HSSR. A point of service can be defined as a place that is frequented by the patient or is close to services that provide access to treatment (such as the premises of a community organisation that works to prevent STIs, supervised injection services, day centres, etc.).

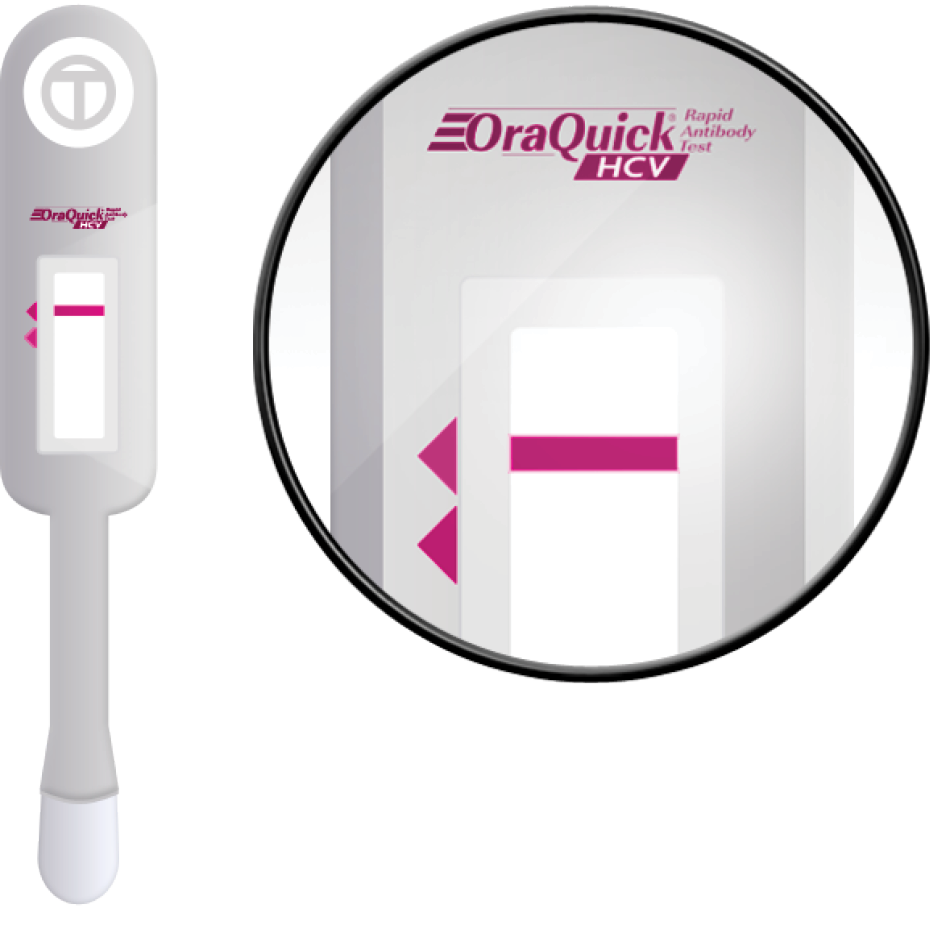

OraQuick HCV rapid testing devices have been approved by Health Canada since January 2017. These tests are over 99% reliable and detect the presence of hepatitis C antibodies using a drop of blood taken from the fingertip. A negative result confirms that the person tested is not infected with HCV; a positive result indicates the presence of active or past HCV infection (25% of people exposed to HCV recover on their own without treatment, but anti-hepatitis C antibodies remain in the blood and cause a positive result on the OraQuick rapid test). Reading the result of an OraQuick test is similar to reading a pregnancy test or the COVID-19 self-test.

If the result is positive, a second test to detect the RNA of the hepatitis C virus is required to confirm chronic infection. Rapid testing therefore do not provide a diagnosis to the person tested, but are a preventive tool to detect possible cases of hepatitis C. They can also be used to refer people to the health and social services network (RSSS). Community testing is not intended to replace the medical sector and its expertise in the treatment of hepatitis C; it would only make it possible to expand the range of testing services available to detect infections still overlooked by the current system, while offering new opportunities for the community and the health network to work together to eradicate hepatitis C.

Fast testing at the point of care allows us to offer testing as a preventative tool in more settings and on more occasions. Getting results within 20 minutes is also a significant improvement, preventing people from being lost to follow-up before treatment has even started.

HCV disproportionately affects marginalized communities. In 2019, the Canadian Hepatitis C Network published a guiding model to guide and detail the elimination efforts to be undertaken to achieve the goals set by PHAC. This model proposes targeted interventions around six priority or key populations that are disproportionately affected by HCV in Canada.

These communities are more severely affected by HCV because its mode of transmission is blood-borne. Sharing drug injecting equipment is a major vector of transmission, which explains why 85% of new infections now occur among injecting or inhaling drug users (IDUs). Prisoners are also considered a priority population because of the high prevalence of drugs in prisons and other risk factors such as home-made tattoos and close proximity to prisoners. It is estimated that almost a quarter of them are or have been HCV carriers.

The use of non-sterile medical equipment or medical procedures, such as blood transfusions, that took place before HCV was discovered explains why immigrants from countries with unsafe medical practices and people born between 1945 and 1975 are also part of the main HCV communities in Canada.

Other communities are considered a priority due to socio-economic factors and marginalisation. This is the case for First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, who are five times more likely to be infected with HCV than the rest of the Canadian population, and who are over-represented among people with HCV or who have been incarcerated, two risk factors for hepatitis C. The emerging priority community for gbHARSAH men (gay, bi or men who have sex with men) is called this because, although HCV is not generally sexually transmitted, the number of new infections in this group is rising at an alarming rate. It is estimated that 5% of them have current or past HCV infection.

Eliminating HCV as a public health threat requires a targeted approach with tailored strategies. Community-based harm reduction and STBBI prevention organizations have decades of experience and trust with these communities. They run harm reduction programs for drug use, such as distribution of disposable equipment and management of supervised injection sites. They also focus on education and STBBI prevention in the LGBTQ+ community, address marginalization of First Nations, and help integrate newcomers. These efforts demonstrate their ability to reach groups that are often disconnected from the health care network and to maintain long-term contact, which is critical for effective recovery.

In Quebec, several community health projects aimed at improving access to hepatitis C screening and treatment are already under way (see annexe). Organisations working with key populations affected by hepatitis C have been able to build relationships of trust with the people who use their services. They also offer them support and guidance through the various stages of the HCV care cascade. These programmes are specially developed to meet people's needs in terms of timetables and accessibility of services, as well as a caring environment that helps to combat the stigmatisation of people living with HCV.

However, despite these efforts, the scope of current projects remains severely limited by the cost of hiring health professionals to provide screening and by their limited availability at a time of labour shortages, as community workers are unable to offer testing themselves. Allowing community workers to carry out testing themselves would greatly increase the frequency of these activities, as well as the number of people they could help to recover in an appropriate environment.

The community sector will be able to play an even greater role in this effort if we are given the opportunity to offer these rapid HCV tests ourselves to people who already frequent our organisations and with whom we have already established a relationship of trust. This would also speed up the start of hepatitis C treatment for those who are most excluded from the health system.

This initiative would also have a positive impact on the healthcare system as a whole by reducing the burden of HCV testing, which currently falls solely on nurses and doctors. Currently, the OraQuick rapid tests can only be administered by a nurse or doctor, resulting in significant costs to the government and constant mobilisation of healthcare professionals. The current system presents many barriers to access, particularly for people with mobility issues. The shortage of staff in the medical system is also reflected in waiting times of sometimes several months in some regions before being able to access testing, and then long weeks before receiving the results. These delays are a major source of stress for people waiting for their results, which means that some of them simply choose not to access these procedures that are so inappropriate for their needs - a vicious circle that needs to be broken.

Today, we strongly support the expansion of community-based STI prevention and harm reduction organizations to conduct OraQuick rapid tests. Community workers are well positioned to reach these communities and provide a comprehensive approach. This would allow health care workers to focus on advanced hepatitis C care and ensure better patient follow-up. It also frees up their time to address other public health issues.

The community sector's role goes beyond just testing. It's crucial to offer two key services, rapid testing and support for referrals to the health system (RSSS) These combined efforts can create real, lasting change. This approach is necessary to address a long-standing issue.

There are many multidisciplinary projects that combine expertise to support people throughout the hepatitis C care process. One example is Project Lotus, which ran from 2016 to 2019 in Montreal. This project aimed to provide a personalized and safe alternative for those facing discrimination in the healthcare system. It offered quick access to caring health professionals, accompaniment to medical appointments by community workers, advice on liver-healthy eating with a $100 monthly food budget, and reimbursement for public transport to remove mobility barriers to treatment.

Knowing one's hepatitis C antibody status does not necessarily mean starting treatment when people are facing other more immediate difficulties, such as economic insecurity. The ability to support and respond to the other needs of people living with HCV until they are cured is an undeniable asset offered by the community sector in these projects. Enabling care workers to initiate the cascade of care by providing initial screening for hepatitis C is the next logical step.

People living with HCV face multiple forms of social stigma. This stigma continues in the medical environment, exacerbating the burden of HCV and keeping many patients away from screening opportunities. This deprives them of treatment and the possibility of a cure. It is important to work to limit the negative effects of stigma on health, something that the community has been doing for decades. The community organisations behind this plea, for example, have already established hepatitis C service corridors for users of their centres. These corridors include healthcare professionals with whom the community has established a relationship of trust, and who have experience of providing care to people in a safe, non-judgemental environment. In the event of a positive result from a rapid test, the organisations also have the capacity to refer the person to the RSSS and support them through the rest of their care.

It is also important to ensure that the professionals who carry out the rapid tests are trained in the technical aspects and psychosocial support. As part of its hepatitis C treatment programme, CHUM already offers training in the use of OraQuick rapid tests to nurses who wish to offer this service to their patients. As a community organisation with a provincial mandate for hepatitis C control and prevention, CAPAHC provides training to the various stakeholders who work or are likely to work with the populations most at risk of contracting hepatitis C in Quebec. The training needs of community workers also provide an opportunity for collaboration between the community sector and the RSSS.

The opportunities for the community and HSSR to work together to eliminate hepatitis C are numerous. Rapid testing is only the first step in a long cascade of care. Simplifying access to it would therefore go some way to relieving congestion in the health sector. However, the expertise of the community can ensure an adapted service offering and personalized support in pre-established care corridors.

Several countries have already taken the step of providing rapid HCV testing in facilities frequented by key populations. The approaches vary by context, but they're in line with the WHO Global Strategy 2030.

In 2020, Australia approved and funded the implementation of a national point-of-care testing program for hepatitis C, with the aim of being able to expand and standardize the community screening initiatives already authorized on its territory. The program began in January 2022 and aims to increase testing opportunities and improve patient follow-up at different stages of the care cascade.

The United States has decided to make rapid self-tests for the detection of hepatitis C antibodies available over the counter. Several options certified by the U.S. health authorities are available for sale, with costs ranging from US$59 to US$79 for a self-test kit and the option of consulting a doctor at the service via telemedicine in the event of a positive result. While this approach helps to diversify the range of testing services available, we believe it also presents a number of challenges, as it does not address the barriers to access to HCV testing. It is also economically disadvantageous because of the cost of the tests, and it only targets people who are already aware of the modes of transmission and risks of HCV and are actively seeking testing. Self-testing also poses new challenges in terms of follow-up and referral.

France has implemented a program called TROD for rapid HIV and hepatitis testing. The Haute Autorité de Santé recommended its approval in 2014. A ministerial decree in August 2016 implemented it to combat HIV and HCV spread. In June 2021, the program expanded to include hepatitis B testing. The decree outlines required training for test providers. It establishes an accreditation agreement for trained participants. Training is open to staff, interveners, and volunteers working with key hepatitis C populations. AIDES, a community organization and Coalition Plus member, will offer these training courses.

These examples of alternatives to conventional HCV testing may be useful in determining which options would be appropriate to adopt in Quebec, taking into account regional specificities. We believe that a strategy of empowering, funding, and training community interveners to conduct rapid screening within their organizations would enhance HCV elimination efforts by multiplying opportunities for action to detect new cases and link people to the HCV care cascade.

Rapid antibody testing is one method of action within a global strategy to eliminate HCV as a threat to public health.

Considering :

- Harm reduction materials are already distributed by community organizations;

- The fact that members of key populations already regularly frequent community organizations and that relationships of trust have been established;

- The ability of the community to reach members of key populations and thus inform them and deploy rapid tests among them;

- Forms of stigmatization experienced by certain members of key populations, leading to breaks with the conventional medical environment;

- Multiple difficulties in accessing HCV screening ;

- Easy access to service corridors already established by community organizations;

- Service interruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated Quebec's delay in eliminating HCV;

Authorizing community interveners to perform rapid HCV testing would be a major step forward in the province's hepatitis C management strategy and would help achieve the WHO's 2030 targets. The cost to the Quebec health care system of doing nothing about HCV until it is eliminated at the current rate is estimated to be approximately $31.2 million. Empowering community workers to perform rapid HCV tests is the necessary first step in stemming the public health threat posed by the epidemic.

This appendix provides a summary of hepatitis C projects implemented by the community in recent years. It is a record of the community's positive experience in reaching key HCV populations and providing services that meet people's needs. This list is not exhaustive.